Interview with Anne Lilly as told to Gilmore Tamny.

How long have you been in Boston? Any observations on the Boston arts scene? How the number of universities affect the production of art, artist space, etc.?

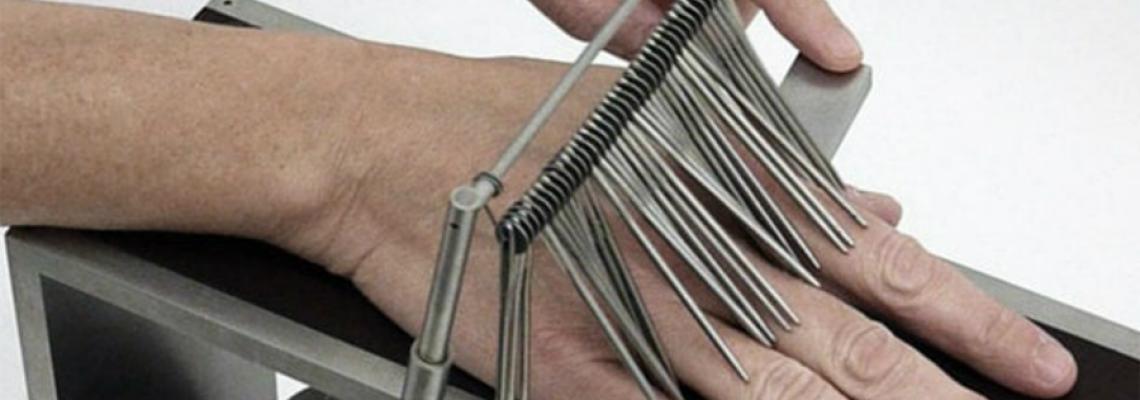

I was raised in the West — Idaho, Oklahoma, Texas, Wyoming, Colorado — and moved to Boston twenty-two years ago. Growing up I had always been magnetized by Boston, at first just because of its distance from where I was! But gradually also by its history, its tradition of liberalism, and its rank as a cultural, intellectual and scientific hub. I arrived here as a newly minted architecture graduate, but the City provided many aids to begin making art and finding my way forward on a different path. Although I hadn’t studied art in college, I always kept a tiny desk-top studio in my bedroom and worked on projects in paper at night and on the weekends. As I began to want to learn more about art, Boston had a richness of sources to explore, and I took metal-smithing classes at the SMFA, welding at MassArt, and machining at Wentworth. Discovering metals meant I could no longer work at home and would need to find “workonly” artist space. It was about 1997 when I got my first studio, in the Fort Point neighborhood in South Boston. There were hundreds of artists in this tiny area; Fort Point brought me so many opportunities and friendships. It was a safe, nurturing place to make art, watch others, learn through osmosis, and grow through participation in Open Studios and the arts initiatives that frequently took place through FPAC and independent collaborative projects.

I was raised in the West — Idaho, Oklahoma, Texas, Wyoming, Colorado — and moved to Boston twenty-two years ago. Growing up I had always been magnetized by Boston, at first just because of its distance from where I was! But gradually also by its history, its tradition of liberalism, and its rank as a cultural, intellectual and scientific hub. I arrived here as a newly minted architecture graduate, but the City provided many aids to begin making art and finding my way forward on a different path. Although I hadn’t studied art in college, I always kept a tiny desk-top studio in my bedroom and worked on projects in paper at night and on the weekends. As I began to want to learn more about art, Boston had a richness of sources to explore, and I took metal-smithing classes at the SMFA, welding at MassArt, and machining at Wentworth. Discovering metals meant I could no longer work at home and would need to find “workonly” artist space. It was about 1997 when I got my first studio, in the Fort Point neighborhood in South Boston. There were hundreds of artists in this tiny area; Fort Point brought me so many opportunities and friendships. It was a safe, nurturing place to make art, watch others, learn through osmosis, and grow through participation in Open Studios and the arts initiatives that frequently took place through FPAC and independent collaborative projects.

Around 2000, fortune brought me to a little old man in Dorchester, Peter Lindenmuth, an engineer who had his own machine shop. Peter enjoyed mentoring and sharing his knowledge and equipment with young people who wanted to make things. Independent Fabrications, the bicycle frame builders formerly of Somerville, got off the ground in his shop. I worked with Peter for three years; under his guidance I got my machining chops down, and he was incredibly supportive when I set up my own machine shop. It was scary to commit myself to the stewardship of tons and tons of aging mid-century machinery and tooling.

Most recently, I’ve fallen in love all over again with MassArt, and am taking casting classes there now. The College has a miraculous foundry/sculpture studio, richly appointed, with incredibly experienced and knowledgeable instructors. In addition to developing new ways of thinking about sculpture and working with materials, I love laboring alongside young artists at the beginning of their careers.

About Somerville in particular — there is an invigorating density and vitality to the arts scene here. The building that I work in has a wonderful mix of artists, designers, light industry and martial arts. Vernon Street is also an enormous anchor of studio space in the community. Yet, while there is interest in and talk about securing affordable work-only artist space for the long term, the City of Somerville keeps passing on the dwindling opportunities to do so. With such explosive property values, I worry that Somerville will be just like every other former artist neighborhood.

Who are some of your favorite artists, those who were an influence? Any local artists?

The artists I am thinking about change over time. Early in my career I was inspired by Minimalism and the California Light & Space movement, artists working per-ceptually rather than con-ceptually. The paintings of Agnes Martin have kept me coming back over and over again. Her paintings have a way of ironing your mind out flat and dispersing it over the field of the painting — so meditative. Locally, Arthur Ganson’s permanent exhibit at the MIT Museum was an important event when I first saw it. Here was someone with strong technical skills, which he was using for creative expression. That was a revelation and helped me to have faith that it would be possible to pursue art, even though I had studied engineering and architecture in college.

One story I would like to share: Having been raised in the Republican Hinterlands, I had no exposure to contemporary art growing up. When I was seventeen, I arranged a short-term exchange program for myself, a one month family-stay in France. In Paris we visited the Pompidou Centre, where I encountered the artwork by On Kawara, One Million Years. It was an array of ten thick black books all lying open on a white table. Five of the volumes were counting down from one million to zero, with “BC” after each number, the other five volumes were counting up from zero to one million, likewise with “AD” after each number. So each page of each book was filled with a matrix of these tiny marching years. I rambled though the books until I located the one that had the “0”. Just a couple of pages to the right of it was the number “1966 AD” — the year I had been born. Shockingly close to that, “1983 AD”, the current year it was then. And next I saw my entire future lifespan laid out like a few postage stamps! In this ocean of years! Outwardly, the artwork was no more imposing than a collection of phone books, but inwardly it was a graveyard for me and for all humanity. I was devastated. Albert Camus wrote, “A man's work is nothing but his slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” On Kawara’s artwork awakened me to the fact of mortality, and to the power of art. It laid a seed that opened much later. I dream one day to make a piece half that effective. Although I don’t work in a conceptual vein, it is important to me to make art that is quiet, deep and — oddly — still.

I find your work is wonderfully hypnotic among other things. Are you consciously trying to make it have that quality or is it a happy accident of what you are doing?

One of the advantages/disadvantages of not having studied art in the academy is that I was never trained to use words to formulate what I wanted to do, inform what I was doing, or justify what I had done. So words and concepts are not part of my process, and the work can arise from a place that is personal, intuitive and non-verbal. Hypnotic effects were not something that I consciously decided upon before starting any particular piece, but after working for twenty years, it is clear that it is a state that I’m searching for, an experience I want to feel myself and share with others. It is neither accidental nor strategically conceived, but something that I grapple toward again and again. Movements that are flitty, jangly, wobbly, jerky, monotonous, or otherwise aversive — these are all possible qualities which appear as a piece develops. But they are also qualities that abound in the world. In a way I think I want my work to be a refuge from the world, from chaos, noise and aggression. I actively steer the work away from that, and instead toward movements that are complex, organic, absorbing, unified, and meditative.

One thing about my work that seems to surprise people: I don’t use a computer at any point. The process is entirely hands on and involves long stages of experimentation. I do sketch a bit to figure out a difficult detail, but the larger action of the work usually does not arise from preconception or pre-planning.

How site-specific is your work? How do you see them relating to their environment?

Excepting two installations, my work so far hasn’t been site-specific, but it benefits from a visually clean environment in which to be seen. Within that, there are still many possible “tones” that can occur in a particular setting. One of my favorite placements — this is going to sound weird — was in a bathroom. The collectors had a seaside summer home on the Cape, and the house contained a fantastic collection of contemporary art. The couple wanted a large piece of mine for their master bathroom. It seemed odd at first, but when I saw it in person, I understood that they would be experiencing the sculpture in their most private moments. That idea — the aloneness, the nakedness, the “being-with” the humble facts of one’s own body — it is actually a uniquely intimate space in which to engage someone through art.

What has been your favorite description of your work or compliment you've received either by respected colleague, random stranger, small child?

Sometimes I am invited to share my sculptures with math classes in high schools or middle schools, and a few years ago I visited the Jeremiah Burke High School in Dorchester. The children there come from poor families, and there is a disproportionate share of hardship in their lives and violence in their community. The teacher who had invited me polled the students for written responses after each class, and he shared them with me. Here are a few of their impressions:

"I liked how she was very creative and how perfect it all came out."

"When it moves I think the parts will touch each other, but they don't."

"I thought on the new word cinema/kinematic, or how objects move on their own."

"How difficult and interesting those sculptures are."

"I thought they had something inside that kept them moving."

"I thought it was cool. I liked it! It was dope because it was different."

"I thought that I could use these ideas to help me relax."

It meant more to me than anything, to know that my work had given these young people

an experience of art that was open, affirming, and meaningful to them.

Below are links to Anne's work:

Anemone:

https://vimeo.com/113636338

Eighteen Eighteen:

https://vimeo.com/111168512

Request for an Oracle:

https://vimeo.com/111168512

Wefan:

https://vimeo.com/95555143

To Caress:

https://vimeo.com/19396356