September Artist of the Month Amber Davis Tourlentes, interviewed by Charan Devereaux

Amber Davis Tourlentes is a fine art photographer and professor at the Massachusetts College of Art & Design. Previously, she taught at Princeton University, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Emerson College and Harvard University, where she received the Derek Bok Center Award for Undergraduate Education Teaching.

Some solo and group exhibitions include the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mills Gallery Boston Center for the Arts, Smith College, Lesley University, Danforth Museum, Harvey Milk Institute. CA, Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, Circa Gallery, Montreal, and Boston Public Library.

Amber received her MFA from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 1998. She also received her BFA from UMass Amherst in Photography and Art History, attending consortium colleges: Smith, Amherst, and Hampshire College.

When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

Probably when I was a young teen, during the AIDS epidemic. My father, who is gay, had a long-term partner, and neither of them got sick. But some of our close friends got sick and passed away. We didn’t know nearly as much about AIDS in the 80’s as we do now. And it reminds me of today and what my kids are living through in the coronavirus pandemic, the dynamic information, and the unknowns. So much of what gay men experienced was not seen in mainstream media at that time, but the contemporary art world embraced the stories of those who were sick with HIV or died from AIDS.

A few years later, during early art classes at UMass Amherst, I went to see the Robert Mapplethorpe show at the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Art Boston] with my father. It was 1990, and it was the last exhibition of a highly controversial traveling retrospective of his work. Mapplethorpe had died of AIDS and there was a mainstreamed conversation about the intersections of his photographic prints, National Endowment for the Arts funding, art censorship, and the AIDS epidemic—all of this was being discussed in the public sphere because of contemporary art. The exhibition was powerful for the Boston gay community, I remember the day we went, there was a line wrapped around the old fire house building to get in. It was a quiet, gray, somber Sunday, and people were running into one another, hugging catching up. For all those visiting the exhibition who had lost loved ones to AIDS, it felt like a memorial. At that time, I remember feeling like only in art photography was this world of beauty, loss, sexual identity, and personal aesthetic accessible to the masses. Photography for me as a young person was illuminating why museum and art spaces are important, like secular gathering spaces of contemplation, safety, community, and acceptance.

Soon after, I took a photography class in Florence, Italy through a university travel program. This was during the 1991 American-led invasion of the Gulf so not many American students attended. I had a darkroom and studio all to myself and met students from around the world who were studying all kind of visual and performing arts. I was able to try beautiful European fiber papers and developers. I would go from making studio portraits of friends to learning the chemical darkroom–all in a single day. This is also what I love about newer digital cameras and inkjet papers: I can do it all in a single day, and in the same space right here in Som erville.

erville.

How did you make your way to Somerville?

I did my undergraduate and then later graduate work in western Massachusetts, and between studies I started an arts & entertainment magazine with a group of friends. Through these accumulation of experiences as photo editor, and fine arts student, I was able to learn all about color negative, Cibachrome, reproduction printing, and also work again with beautiful papers, experimenting with alternative processes and large-scale silver printing. Through the consortium schools at UMass Amherst, I made work and studied art history at Hampshire, Smith, and Amherst colleges, with incredible photo history courses and archives.

After my MFA, I wanted to shift to teaching so I could continue to be in studios, photo art libraries, and museums. My first adjunct teaching position was at Princeton University. I loved the students, archives, and resources, and of course being so close to New York. But it was late 90’s so I didn’t make enough money to live in New York, and driving back and forth from Western Mass was hard on my body. At the time, I was living cheaply with friends in an old mill in Easthampton, and couch surfing in New York, but I wanted to keep living and working affordably, and felt like I could do all in the Boston area.

To back up, I grew up part time in late 70’s/80’s South End Boston: a pluralistic, heterogeneous, area including artist, gay community, so I had enough contacts to land in this area.

I experienced first-hand what gentrification looks like in South End. This is a good moment to mention that I, like many parents, teachers, and creative types, hope that our cities remain accessible, with affordable live/work spaces and good public education for children or our own educational pursuits. And I should also mention talking to you, Charan, that I love living so close to a place as special as the Somerville Museum. It is wonderful how the city’s high school students and teachers have activated the Somerville Museum archive and space. I’m also really excited about what I have seen online about plans such as Art Farm. We love the Somerville Art Council’s Porchfest and all the arts festivals our city has to offer for all 8 to 80!

Can you talk about some of your recent work?

There are two projects that are very new, which connect to our conversation thus far. The first project came up during quarantine. I had a growing stack of art auction house catalogues sent to me over the years by a friend who worked with me at the magazine I mentioned. I started cutting them up, montaging well-known reproductions of imagery from these catalogues, works that are recognizable from the 20th-21st century photo history blue-chip version of photo-canon. [“Blue-chip” refers to art with high economic re-sale value.] It was so relaxing, placing these images like puzzle pieces on my table, sometimes my kids and husband would join in with composition shifts, and I would photograph them.

At the same time, I was walking around Somerville and photographing houses that were getting stripped, rebuilt, flipped, or enlarged to make more units. I loved the shapes stripped down clapboard structures make: like puzzle pieces being enlarged on a lot, so I have been combining all in photoshop. I just assigned daily project to students, so this will be mine for the fall! Playing with these extracted house shapes, like the cut-ups of auction house photo magazine, I couldn’t help but feel privileged. Unlike my husband I worked remotely all last year, we felt so lucky to have jobs, roof over our heads, and my husband and I be able to keep kids safe. For inspiration to keep going with it I have been looking more at the history of Avant Garde Photomontage: investigated class, labor, trauma, love and loss. This is why the working title is photomontages: houses + auction house catalogues.

The second project, which is equally new, came about because of the time I had at home with my teens during our remote teaching and learning. We would have these funny conversations driven by their interests. My kids, perhaps like many, are intrigued and apprehensive rightly so about newer digital currencies like Bitcoin. As they were teaching us about why digital mining was bad news for the climate, and land fill, and a poor use of technology, we were also researching the history of American currency. I found Cranes Paper Making Museum in Western MA, it’s a terrific mill museum visit by the way, I highly recommend for all ages. And this leads me to an older connected project, my mother is a conservator and gilds for some of her clients, and she had given me her extra precious metals patent sheets. I started gilding heavily gessoed canvases that I sewed around the edges, gilded with silver, gold, and platinum to create floor cloths you can walk on. I wanted them to be walkable and functional, so they are 6 feet by 6 feet. I liked how these shiny precious metals (problematic, colonial, toxic since they’re mined) can become perhaps more useful, to stand on, or to use as a tool for keeping people physically together.

physically together.

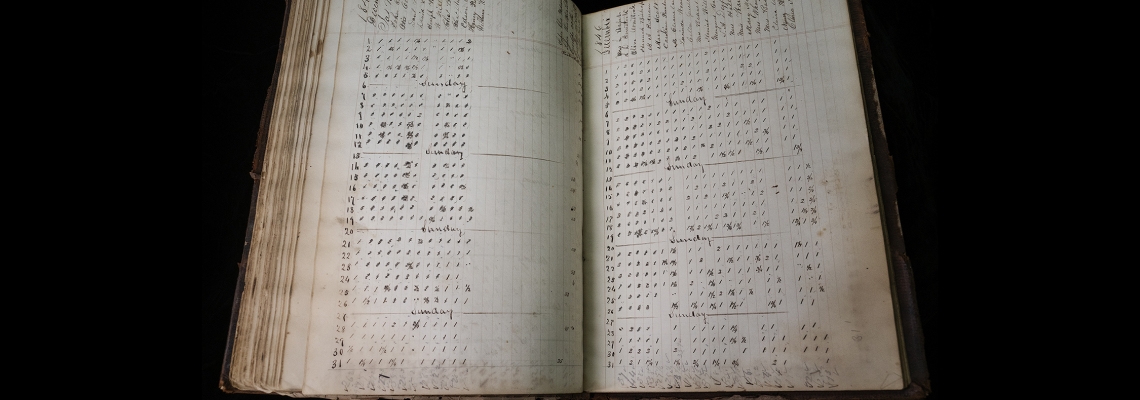

But back to the Cranes Museum. I’m just at the beginning of understanding currency histories. There is so much at the museum to explore, such as ledgers, one seen here from the late 1700s that shows how Paul Revere bought paper to pay the revolutionary soldiers. He was a silversmith by the way; his family business often struggled in Boston’s North End. Also photographing pre- and post-Civil War era currency, when money was made and controlled state by state and then federally through various acts of Congress. I started reading more about counterfeiting, which has to do with early photography—40 percent of money during the Civil War was counterfeit. President Lincoln and the U.S. Senate federalized money, an attempt to end the constant violent atrocities of slavery by creating nationalized controlled capital and currency to protect all Americans. There is so much more to learn here and digest. A lot of my interest was inspired by my son’s AP U.S. History class at Somerville High School. He is so much more enlightened than I was at his age.

I’m also interested in the histories of paper currency itself, which was made from Southern cotton that was used in Northern textiles, and with the leftover rags sometimes sold to paper mills to make pulp for paper. Textile millworkers and those living near Cranes in Dalton, MA could sell leftover back in the day to the paper mill. Perhaps the phrase “rags to riches” comes from this? Another ledger detailed how much each millworker made that day, who received money for leftover fabric, and how much money was received by selling paper to clients like the mint. These ledgers contained everything that happened in and out of the mill that day, that year, all in one book, kind of an amazing one-of-a-kind object and perhaps made with their own paper. So non-fungible, maybe, if I really understand what that actually means?

Some of the imagery is really charged, the Georgian money from the 1860’s, with faded stamp ‘back by gold’ almost looks wounded, as if bandaged together. As someone who grew up in the LGBTQ community and has photographed the civil-right-to-marry movement – accomplished right here first in the state of Massachusetts – I am interested in how this currency archive could explore states’ rights, federal laws, and histories of power, wealth and labor. I look forward to going back and photographing more. I’m working with a wonderful director at Cranes named Jenna Ware. She and those who have worked at the still mill, some for many decades give tours, explaining how the watermarks on the paper were made and by people in the mill, not classically trained artists, but people working from photographs. I love how democratic the medium of photography is.

How does teaching inform your work?

MassArt has been the perfect spot for me, teaching in a multidisciplinary foundation program. I love working with first year students, and some are the first in their families to attend college. The work I make is completely informed by what I learn alongside my students and colleagues. For example, this paper currency archive project is also inspired by a student design project.

Massachusetts has the only freestanding four-year public art and design school in the country, and we have a new public museum. There is so much public-facing engagement from MassArt for students and families preK-16. I do love living in the Boston area, not only because there are so many cultural education institutions and all so close but we also have a thriving creative Arts Council community, and so many good trades, artisans, creatives including open studios, festivals, farmers market, and places like Parts and Crafts for kids. There is always cultural production happening, and always ways for us as a family to engage creatively. We are unfortunately losing the Artist Asylum to Alston I think, but it’s bike-able!

This September, back to school feels particularly intense, I’m so thankful to be teaching in person, and with my kids in school. It has been an extremely challenging couple years for everyone, and more challenging for families with littles under 12 this fall, and those who are most impacted by losing family members, long Covid, constant climate and economic challenges.

Cultural and Arts Councils provide room and space for so many wonderful performing arts, visual and public art collaborations by young people, and all ages! I’m optimistic for September’s new school year! Thank you for this opportunity to talk with you and works shared with you Charan, you are wonderful!

Artist information:

ambertourlentes.com