Interview with Mario Quiroz-Servellón by Charan Devereaux

Mario Quiroz is a documentary photographer. He was born in San Salvador, and relocated to the United States in 1999.

For the last 14 years, Mario has been exhibiting non-stop throughout New England. His projects “Immigrants in New England: An Old American Tradition,” “Domestic Workers: The Invisible Wheels that Empower our Economy,” “Immigrants: A Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” “Travelers: Love Tales from Salvadoran Immigrants,” “Aging Minority in Massachusetts,” “Mis Vecinos: Portraits of Fitchburg’s New Latino Communities,” and “1World/1University: Diversity at Lesley” have been exhibited in more than 25 different locations. He has worked in partnership with MIRA Coalition, Centro Presente, the Student Immigrant Movement, Chinese Progressive Association, the Dominican Development Center, the Massachusetts Coalition for Domestic Workers, the Brazilian Immigrant Center, the Massachusetts Alliance of Portuguese Speakers, the Boston Workmen's Circle Center for Jewish Culture and Social Justice, Community and Labor United, SEIU 32BJ, and AFL-CIO.

His work is currently on view at the Somerville Museum in the exhibition “Museo Inmigrante: Stories of Resilience from Somerville’s Padres Latinos” (January 12-March 23, 2024). Mario’s photographs are part of the permanent collection of The Commonwealth Archives & Museum and the Fitchburg Art Museum.

Mario holds a Bachelor's Degree in Liberal Arts with a specialization in Documentary Photography from Lesley University and a Master of Fine Arts in Visual Arts from Lesley University College of Art and Design. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts and has worked in the Somerville Public Schools (SPS), or in partnership with SPS, since 2014.

Do you remember when you first knew you wanted to be a photographer?

Yes. Initially, I was trained as a poet. My artistic sensibilities were awakened through poetry workshops. I went to a youth center and joined a poetry club when I was 16 years old. I am not a good dancer, and I couldn’t play an instrument. When you are a teenager, these skills are your resources when talking to girls. Since I didn’t have those skills, I had to be very poetic when I spoke. From there, I took more classes, and learned to discover deeper emotions and ideas, and started writing poems about something different, something higher.

When I moved to the United States [in 1999], there were two things I was sure of. I wasn’t going to drop my second last name [Servellón]. It is part of my core identity. And I wasn’t going to translate my poetry. It came out of my heart in Spanish and I wasn’t going to rewrite it in English. So my artistic alternative became the visual image. From the poetic image to a visual image. That is the moment [I knew I wanted to be a photographer].

Looking back, there is another important moment. At first, I didn’t go to photography school, so I started learning from books. The first book I got was Ansel Adams’ The Camera. In the chapter on small cameras, there is an image by [Henri] Cartier-Bresson, a picture of kids playing in Sevilla, Spain after the war [in 1933]. Cartier-Bresson framed the children through a hole in a wall made by a bomb. The boys are playing tag, and one of them is running on crutches. So we can see the struggles of war, the destruction, even a child who is hurt, but what we see most is the joy, the innocence, the life. This is what I love about Cartier-Bresson, how in one image he can tell the story of something painful with an uplifting perspective. Yes, it is hurtful, but there is life afterwards. When I saw that picture, I knew this is what I wanted to do.

Cartier-Bresson and Sebastião Salgado are my favorite photographers. Salgado is closer to me, he is very alive, he is from Brazil, he explores French culture and English culture with an accent, the same way I do. But that has never stopped him from doing things.

Can you talk about your early experiences as an artist?

Life is not a straight line. We don’t live experiences in linear ways. We live different experiences simultaneously-- as if we are learning three languages at the same time—that is how we navigate life. El Salvador has a heavily European educational system. When I was in school, classical art was what was deemed beautiful, modern art was not. Ancient Roman statues were OK, but those of the Aztecs or the Incas were not celebrated as artwork. That is how we were taught. It was my experience coming up. It took a lot of effort on my part to remove that lens. Even today, I’m always aware of that filter, the traditional Western concept of beauty. I lived in Miami for five years. One of the things I realized I did not want to do was photograph palm trees, beaches and The Everglades, that was not for me. If I stayed in Miami, based on who I was and my reality, I would have stayed doing that, and I didn’t want to.

What did you want?

I wanted to photograph life, people, cultures, experiences. The first time I went back to El Salvador, I took a camera with me. Probably my favorite picture I ever made was from that trip. I took it on July 10, 2003, I have a good memory for da tes, I flew in on a Saturday and took it on a Tuesday. It is a picture on an archaeological site, an ancient place. A high city that is connected though a river with the village of Joya de Cerén, the Salvadoran equivalent of Pompeii. A volcano erupted and people were petrified in lava. My picture is of boy who lives nearby with his brother, and they would take their sheep up near the pyramids and play in the ruins. In the image, he and his dog are standing in the ruins, with a broken piece of beautiful ceramic. For me, it is a perfect representation of what it means to be Salvadoran. To be a kid who has very few material things, while also having plenty of cultural heritage. He is playing on ancient ruins, but he is not aware of what he is standing on, the hundreds of generations that came before him. He is ignorant, innocent to the greater past, but trying to make his life a little brighter. I took that picture 20 years ago.

tes, I flew in on a Saturday and took it on a Tuesday. It is a picture on an archaeological site, an ancient place. A high city that is connected though a river with the village of Joya de Cerén, the Salvadoran equivalent of Pompeii. A volcano erupted and people were petrified in lava. My picture is of boy who lives nearby with his brother, and they would take their sheep up near the pyramids and play in the ruins. In the image, he and his dog are standing in the ruins, with a broken piece of beautiful ceramic. For me, it is a perfect representation of what it means to be Salvadoran. To be a kid who has very few material things, while also having plenty of cultural heritage. He is playing on ancient ruins, but he is not aware of what he is standing on, the hundreds of generations that came before him. He is ignorant, innocent to the greater past, but trying to make his life a little brighter. I took that picture 20 years ago.

I left the beaches and palm trees of Miami and moved to Washington DC in 2005 where my Dad’s family lives. In DC, I got to see the reality of Salvadoran immigrant families, where I could relate and connect. I had the good fortune to work as a communications specialist for CASA de Maryland, one of the largest advocacy groups for immigrant rights in the country. I am not sure how I ended up as their communications specialist -- maybe it was my ability to take reality and put it in a better perspective. While I was there, I was also building my photography portfolio. The director of my department wrote a Ford Foundation grant and included  a small budget for documentary photography. The grant came through, so I got to photograph the immigrant experience in Maryland.

a small budget for documentary photography. The grant came through, so I got to photograph the immigrant experience in Maryland.

I also came up with many photo projects in El Salvador, and I found people to sponsor them. That is how I learned to raise funds and work in partnerships. Also, I did a project in Arlington County, Virginia creating a visual celebration of the local Mongolian community as part of a county grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was the first project I did in another language, not Spanish or English. I was an outsider, but I was similar to them in the sense that I was also from somewhere else. It was a beautiful experience. I was invited to homes. I felt acceptance and welcoming, and that has always stayed with me. We may not speak the same language but we all care and we all want good things.

What brought you to the Boston area?

I was living in Washington and while I was visiting in El Salvador, I met someone through a mutual friend. I photographed her the day I was returning to the US. I came back from El Salvador, and learned there was a project that she could be part of. So she came to DC and we decided to get married. We decided she would get to choose where we would live in the US, and she chose Bos ton. We moved here the week before [Massachusetts Senator] Ted Kennedy passed away. That was summer, August 2009. I remember because we used to live in front of a fire station and they flew the flag at half-mast. I have always lived here since.

ton. We moved here the week before [Massachusetts Senator] Ted Kennedy passed away. That was summer, August 2009. I remember because we used to live in front of a fire station and they flew the flag at half-mast. I have always lived here since.

Here in Massachusetts, I worked on photography projects with many organizations, including MIRA Coalition, the Salvadoran consulate in East Boston, the Commonwealth Archives & Museum, and the Fitchburg Art Museum. Then I went to grad school, which was a good thing and challenging. It was good because it pushed me to try different cameras, formats and approaches. But my expectation was I was hoping to find [a teacher like photographer and educator] Minor White, and I did not find Minor White. Some people were very encouraging, but some were so focused on “new things” that they dismissed my work because it took a more traditional path. Another positive thing that came out of grad school was the deep bonds of friendship with some members of my cohort. I often reach out to them for help, from talking shop about cameras and technology, to exploring ways to improve my artistic discourse, to having deep and philosophical conversations. I am grateful for that.

How would you describe what you do now?

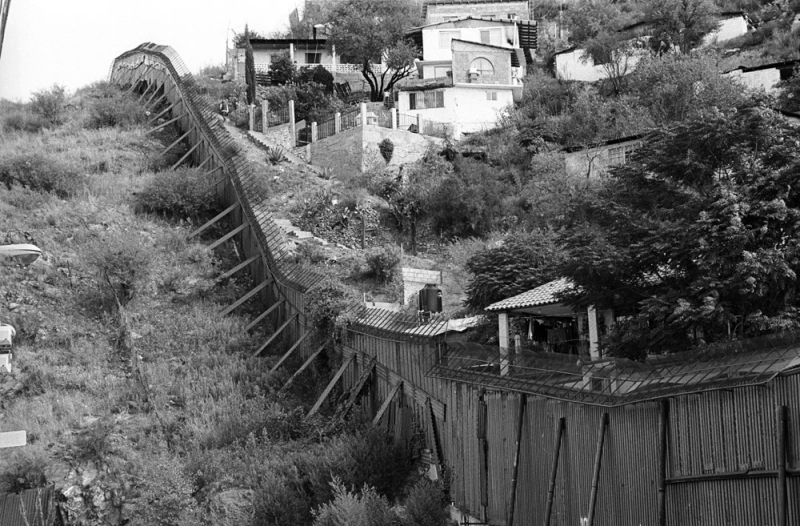

I think Covid changed the dynamic for me. Before Covid, my photography was very people-based. But not having access to people made me look for different things. It made me work more with a 4x5, a large format camera, and see things from a structural point of view. I cannot show people, so I will show their buildings, I cannot show their economic struggles, but I can show the geography of that struggle.

Now, I am going back to photographing people, but from a more geographical point of view. Context matters more than before. I am showing someone in their living room, but the living room has its own history. I am very happy with the way I’m doing things now because I get to play with all kinds of cameras. Switching formats is an amazing exercise. I am very excited, it is new work, it is completely independent from the past, yet it has the same ideological quest, a different way of doing it. I am sure that after a few cycles, a new format will emerge, and I am very OK with that.

Your work is part of the current exhibition “Museo Inmigrante: Stories of Resilience from Somerville’s Padres Latinos” at the Somerville Museum. Can you tell us a little about your images in that show?

the Somerville Museum. Can you tell us a little about your images in that show?

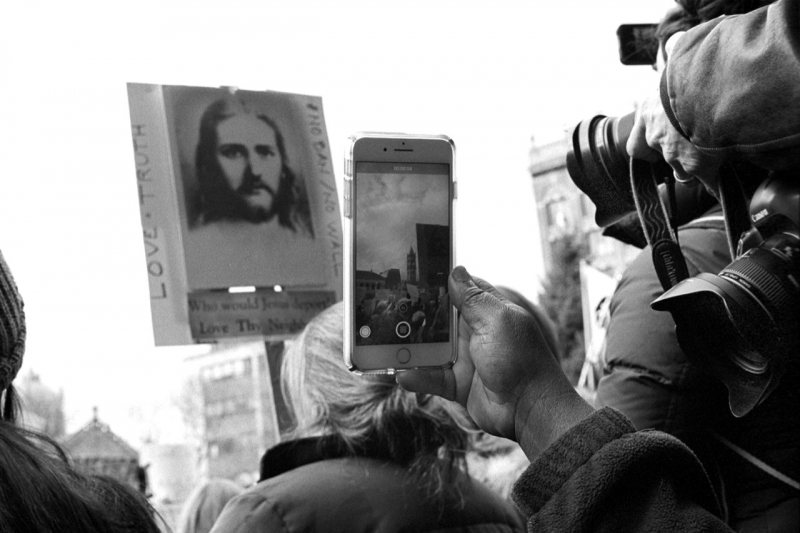

The main idea is to create a more complete version of the immigrant family experience with not only portraits of families inside their homes, but photographs of the places that create community. The images are everyday landscapes, cityscapes that will be there for generations as a reference point for how it is to live in Somerville.

Do you have a new project underway?

Yes, it is called “Home Sweet Rented Home” and it based in Somerville. It is a project with CAAS (Community Action Agency of Somerville) to create awareness and add faces and stories to the struggle that low- and moderate-income renters are facing. The profits of gentrification benefit a few at the expense of the many. You cannot stop progress – you should not stop progress. But there’s no reason why it can’t be more equitable and benefit the new and the old.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I’d like to say a reason why Somerville matters to me. When I was in El Salvador, my teenage dream was to travel and explore the world. Living and working in an immigrant community is like traveling the world within a few blocks. It is a celebration of diversity, of how amazing it is to be different. There are many Salvadorians here. Working with and for them is like finding a long-lost cousin or an aunt I haven’t seen in years or an uncle I was told about, but never met. It is like working with an extended family.

Artist info:

www.marioquiroz.com

Cover photo credit:

Iaritza Menjivar