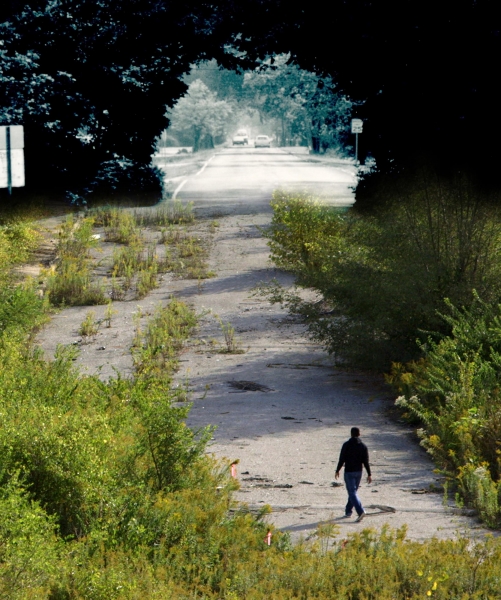

Jane Gillooly is a non-fiction video and media artist. She is committed to the art of narrative, how it is constructed, and how complex and often hidden histories, can be made accessible. What connects her work is an empathetic curiosity about individuals’ struggles, especially when history, politics and personal crises conspire. She grew up in Ferguson, Missouri. Her most recent film, Where the Pavement Ends (2019), examines the shared histories of the Missouri towns of Kinloch and Ferguson, and the deep racial divides affecting them both. Her other work ranges from the experiential in Today the Hawk Takes One Chick (2009), filmed in the Kingdom of Eswatini, to a forbidden love story, Suitcase of Love and Shame (2013), reconstructed from audiotape discovered in a suitcase purchased on eBay. The work that began her career, Leona’s Sister Gerri (1995), deftly pieces together the story of Gerri Santoro’s death from an illegal abortion and whose image galvanized the reproductive justice movement.

Gillooly’s award-winning work has been screened internationally at museums and festivals, including one-person screening/exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, the Museum of the Moving Image, Art of the Real, and the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Other honors include Best International Film at IMAGES Festival in Toronto, and numerous fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, the MacDowell Colony and the LEF Foundation Moving Image Award. Gillooly is a Guggenheim Fellow and a Professor of the Practice Emerita in Media Arts at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University.

Jane Gillooly was interviewed by Charan Devereaux.

When did you know you wanted to be a filmmaker?

I would say I evolved into being a filmmaker, it wasn’t a plan. I went to art school, and was interested in media arts. A lot of my work was single frame images and then I began making single frame artwork that could be reproduced in multiples, like posters. Next, I started to create slideshows, assembling still images in a sequence, which essentially became my first time-based work. Later, I added monologue, and delivered the monologues live with the projected images behind me. That work evolved into a project I thought I’d be able to shoot with a video camera – going inside the MCI-Framingham women’s prison. [MCI stands for Massachusetts Correctional Institution.]

It was very difficult to get access to the prison. In the end, they gave me access but said I couldn’t bring a video camera—I was allowed to bring a still camera, an audio recorder and one assistant. I did a lot of audio recording and cut a 30-minute audio piece before I started layering on my images. I had taught myself how to cut audio in an earlier project where I self-released a 45 [7-inch record] of sound pieces, I learned about recording voice, editing voice and physically splicing quarter inch audio tape. I took my still images [from the prison] and projected them on dual screens in a montage, with the audio track.

I travelled with the artwork, called So Sad, So Sorry, So What, to some galleries and it was cumbersome. There was a computer that ran the slide projectors and that computer was hooked up to a sound system, so it was hard to travel with all the equipment and hire a technical assistant. I’ve never been a very well-funded artist, and I was having trouble reaching an audience.

At the time, there was a cable station called Continental Cablevision, and they were allowing artists to put work on the station. They gave me a grant to convert the multi-image slide show into a video for broadcast. That was the first time I had a single screen work I could distribute or broadcast.

My next project was Leona’s Sister Gerri. That was my first film (video). I was already working in time-based art, so film didn’t feel like a big leap to me. I didn’t even own a video camera, so I bought one a week before I started working on the project. Leona’s Sister Gerri is very locked down, it is not particularly cinematic, the camera was on a tripod most of the time. I was approaching moving image work a little hesitantly. I got funding for this film from the CPB [Corporation for Public Broadcasting] Independent Television Service and it was later acquired for POV [television’s longest running showcase for independent nonfiction films] and nationally broadcast.

My next project was Leona’s Sister Gerri. That was my first film (video). I was already working in time-based art, so film didn’t feel like a big leap to me. I didn’t even own a video camera, so I bought one a week before I started working on the project. Leona’s Sister Gerri is very locked down, it is not particularly cinematic, the camera was on a tripod most of the time. I was approaching moving image work a little hesitantly. I got funding for this film from the CPB [Corporation for Public Broadcasting] Independent Television Service and it was later acquired for POV [television’s longest running showcase for independent nonfiction films] and nationally broadcast.

I was somewhat interested that I could reach more people if I continued working as a filmmaker. I’d always loved film, and watched a lot in college. I moved to the Cambridge area long ago and spent time in the Harvard Film Archive and snuck into the MIT film/video section screenings. Seeing Sans Soleil by Chris Marker at the Harvard Film Archive was massively influential and essay films were very influential in general. I worked at the Orson Welles Cinema on Mass Ave. where I saw some of my formative social issue documentaries over and over, like Julia Reichert and Jim Klein’s Union Maids and Seeing Red. I evolved into a filmmaker and years later joined New Day Films, the filmmaker-owned distribution company that Julia and Jim cofounded with other makers.

Can you talk more about your early influences and what got you on your way as an artist?

I was exposed to art. I grew up in a large family in Ferguson, Missouri, near St. Louis. My mom was always interested in art. She brought me to my first foreign language film when I was a child, less than ten years old. I remember seeing Knife in the Water with my mother, an early [Roman] Polanski film, an intense film, at the St. Louis Art Museum, which was free. She brought us to the museum a lot.

An older sister went to art school, she was ten years older than me. Quite a few of my closest friends in high school were interested in the arts. The group of friends I spent most of my time with, at least five of us were interested enough in the arts that we would go to art school. All of us did and we all graduated. And we are all still working artists.

Early in art school, I was able to meet artists before they were really famous. One of those artists was Krzysztof Wodiczko – I was enamored with how he thought. He works in mobile sculpture and large-scale projections on architecture and monuments. He created an installation for First Night Boston, and I was a technical director for him. He later taught at MIT and he’s produced projects all over the world at this point. His work became more and more interesting to me. It is site specific and extracts narrative information about that site. [In 1998], he created a piece commissioned by the ICA Boston about the unsolved murders in Charlestown, all from the perspective of impacted family members. His film was projected onto the Bunker Hill Monument with massive speakers on the site. It was so powerful and very moving and somewhat frightening. He was combining so many elements, creating an experience within a location where [the murders] happened, fueled by witness testimony, and amplified by the scale of the projection with immersive sound—so many things rolled into one. That kind of conceptually layered work has always been inspiring to me.

There were other artists who have made beautiful work. Janet Cardiff has done incredible sound work, sometimes theatrical, sometimes installed audio like her Forty Part Motet. Eve Sussman made an algorithmic film called Whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir where no one sees the same film twice, it was remarkable. She shot actors and edited scenes but the film which I saw in a gallery is “composed from two screens: one reflecting the ‘movie’ and one depicting the computer program behind the movie.” There is the generative artwork out now doing something similar called Eno [by Gary Hustwit] that selects from a database of 30 hours of new interviews with Brian Eno and 500 hours of film and creates a new film at every screening.

How did you develop your narrative approach?

I’ve always been reluctant to use a voice over unless I was making something from my point of view, such as a monologue, or retelling other people’s stories. I learned early on that I could discover the narrative within what the subject had to say, it worked for me, I was able to edit this way. If I needed more information or was unclear about what they are trying to say, I would ask to speak to them some more. I try to develop deep relationships so the projects can evolve. It is something I feel my way into.

When I’m making a film, I go through a long process of assembling information. Beginning with research but simultaneously visiting locations, filming tests, gathering objects, building an image archive, making introductions, and eventually interviewing people at first for information without a camera and later getting permission from people I hope will speak on camera. This interview process always opens up the story and leads me to other people, archival sources, or ideas for visuals.

In my film Where the Pavement Ends, there are a lot of historical archival sources, such as Congressional hearings and old recordings of girls singing and reciting the Gettysburg Address. These recordings give the work both context and texture without a narrator’s voice.

In my film Where the Pavement Ends, there are a lot of historical archival sources, such as Congressional hearings and old recordings of girls singing and reciting the Gettysburg Address. These recordings give the work both context and texture without a narrator’s voice.

You also worked as a professor. When did you start teaching?

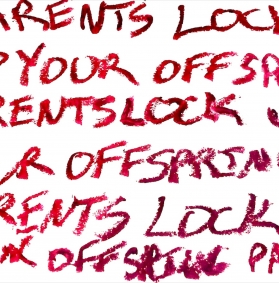

I started teaching at the Museum School [School of the Museum of Fine Arts] around 1990. I was invited to teach a class before I was known as a filmmaker. I was doing a lot of graphic arts and photo-text work, offset printed in multiples for street art or for publication—it wasn’t precious, they were meant to be distributed. I was comingling nonfiction material with images, text, story and picture ideas. I called my Museum School course BREED, a course for reproductive artists. We worked with a printing press and in dark rooms, exploring how to combine text and images and create printing plates. When I started doing more work on slide projectors, I began teaching in a department called Crosscurrents. When I started doing single-channel films, they wanted me to teach video. I wasn’t teaching in a film program. I was teaching in an art school with students who have moving image cameras, but were interested in off-screen uses of moving images and sound. Most of my work is single screen, narrative and highly edited and I was teaching those skills as a foundation for time-based video art making.

By the late 90s I was teaching a lot of courses. When a position became available, I applied for it, and became full-time in 2004.

All the while you were making films you were also teaching?

Yes, which is insane, making a film is more than a full-time job while also teaching full-time, and later chairing the department, it was hard. I did get sabbaticals where a big chunk of my work would take place. I often had deans who were supportive and would give me some professional leave so I could travel and do work while I was teaching. Students sometimes traveled with me, so I tried to have my students benefit as well.

How did teaching inform your work?

Because of what I taught and the way most SMFA faculty teach, my courses were hybrid, both seminar and production. At the time, our studio courses ran for a full day once a week with a two-hour break. You could watch a lot of work together, have discussions, long critiques, and take field trips to see work as a group. The planning that went into my classes necessitated that I know what was going on all over the city. Having to curate, interpret and present contemporary work provided opportunities for me and the growth of my personal artwork. I was in conversation with other artists and scholars across Boston and national and international artists. Some I have since collaborated with. I attended festivals and previewed films I needed to see that could also fit into my Critical Screenings, Archival Verité or Nonfiction Narrative classes. I was often thinking of students and what was essential for them to see and naturally, they were bringing ideas and influences into the classroom that would never have occurred to me.

Because of what I taught and the way most SMFA faculty teach, my courses were hybrid, both seminar and production. At the time, our studio courses ran for a full day once a week with a two-hour break. You could watch a lot of work together, have discussions, long critiques, and take field trips to see work as a group. The planning that went into my classes necessitated that I know what was going on all over the city. Having to curate, interpret and present contemporary work provided opportunities for me and the growth of my personal artwork. I was in conversation with other artists and scholars across Boston and national and international artists. Some I have since collaborated with. I attended festivals and previewed films I needed to see that could also fit into my Critical Screenings, Archival Verité or Nonfiction Narrative classes. I was often thinking of students and what was essential for them to see and naturally, they were bringing ideas and influences into the classroom that would never have occurred to me.

Are there things you find yourself being drawn to now?

Filmically, I’m still interested in nonfiction work sometimes conceived more for the gallery than a theater. But that was as true when I was teaching as it is now. I’ve always read a lot. When I was teaching, I was reading more art theory. Now I’m going back to other nonfiction that interests me like nature.

How did you come to make the film Today the Hawk Takes One Chick?

How did you come to make the film Today the Hawk Takes One Chick?

That film developed out of a friendship. One of my best friends, Tracey Kaplan, is South African, and she had decided to adopt as a single mom—this was in the mid-00s. She realized how many orphans there were because of HIV. She told me about what the situation was like there. How can the communities absorb these children? She didn’t have a lot of information, but her sense was it was falling on grandmothers to care for them. We talked about if there was a film there, about the caregivers, and we decided there was. My friend became one of the producers, and we raised money and made the film. We ended up in Swaziland, now called Eswatini, because one of the contacts we made through Doctors without Borders thought it would be easier to film there, and that turned out to be correct. We made the film over a few years, I visited two times editing after each trip. It was a moving experience to be focused on the grandmothers, whose lives in an isolated rural community were upended by HIV. They were in the process of reinventing their traditional roles. Some were quite elderly and some were young, still raising their own babies.

How did you come to make Leona’s Sister Gerri?

That film was the result of having a very close friend, Toni Elka, who was Leona’s daughter. Toni and I were talking about a reproductive rights case at the Supreme Court, and she mentioned there was a photo that had gone around for decades, and it was a picture of her mother’s sister. [The photo was of a woman who had died in a motel room from an illegal abortion in 1964.] I was shocked, I had seen that picture myself, and I had no idea. I asked Toni if her mom had ever wanted to go public about it and she didn’t, she was very private about it.

Leona changed her mind and asked Toni if I was still interested, so I bought a camera and spent a weekend at Leona’s house. If someone is ready to talk, you don’t tell them to wait. Leona was my introduction to other family members you see in the film. I did research on the photo to see how Ms. Magazine got it. [Ms. Magazine had printed the photo in 1973.] Leona tells her part of the story but she didn’t have all the details surrounding the photo or Gerri’s death. This was my first work conceived as a film where the chronology unfolds in the way the interviews are edited, moving from person to person. Each person spoke to what they knew and then we’d cut to the person who had the next part of the story.

Both of these films grew out of a friendship.

When I think about it, many of my projects have some personal connection. For Where the Pavement Ends, I grew up in Ferguson, next to Kinloch, Missouri. I had no plan to make that film. I’d been gone for so long but I had some of the same memories and formative experiences as people I talked to, who were from Kinloch. I was straddling these worlds. I was a white person trying to tell both sides of the story, and some people in both towns didn’t trust me and didn’t want to talk. Enough people did, and we were able to speak about the racism behind the existence of divided communities. Audiences across the country where black communities are living next to white communities recognized that.

The slide-monologue prison story about El Salvador, grew out of the central American solidarity movement back in the 80s that I was peripherally active in. There was an underground railroad for those trying to escape El Salvador, and the apartment I lived in was one of those stop-over places. That’s how I learned about the women’s prison in El Salvador. I was invited to show that work at MCI-Framingham women’s prison, and the female inmates challenged me. They said “People don’t know we exist. Someone needs to make a film about Framingham.” I started working on So Sad, So Sorry, So What. The HIV crisis was exploding, it was the 1980s, and at the time, it wasn’t widely known that many people who were HIV-positive were female. Many women in prison were IV drug users and had become prostitutes to support their drug habit. About 40 percent of inmates in MCI-Framingham were HIV positive.

Friendships and connections were important in my filmmaking. Through them, I could possibly do justice to a project, I wasn’t a complete outsider.

Can you talk about your thinking for how to construct a narrative?

For Leona’s Sister Gerri, I thought a lot about it during the editing process. When I first made time-based work, I was editing audio. I hadn’t cut a film before—I had been cutting audio and working with images. I worked with [editor] Lisa Monrose on the film, and we decided to cut the audio first. I was cat-sitting at a friend’s place while she was at an artist residency and while I stayed there, I went through all the transcripts and organized them. I started structuring it in two ways—chronologically, including the events that led up to the discovery of [Gerri’s] body in the motel room where the photograph was taken, and thematically, defining the cultural and political realities that we wanted to address, working class women, domestic violence, and reproductive justice. I came into the edit room with mounds of paper for what people sometimes call a paper edit. The chronology was somewhat straightforward. We started when Gerri was young, in Coventry, Connecticut, an immigrant farm family with 15 brothers and sisters. I pulled in interviews that referenced her childhood.

But we also wanted it to unfold in a suspenseful way. The image of her body is seen right at the opening of the film in the context of a press conference, but we didn’t want to build the story from that event. We wanted to use Gerri’s image at a protest rally as the turning point of the film. Leona asked if I could enlarge the photograph and send it to her. She also asked me if I could blow up the words “This is My Sister.” She turned it into a poster and went to a demonstration, with this sign. That was the image that the film needed to turn on. Leona holding the poster which represented both the universal and the personal power of the image. She wanted to make a public statement that her sister didn’t need to die. Gerri left behind two daughters whose lives were destroyed by what happened. The repercussions go on for generations. We edited the film going towards that moment at the protest rally moving forward, rather than the moment in the motel, when Gerri is discovered alone.

We would raise a question, and let each person we interviewed answer as much as they could. If they didn’t know something, we would find someone who did. This pulled you through the film. The motel desk clerk and the chamber maid and the detective who worked on the case. They each addressed their own part in the story. The sad thing was that abortion and domestic violence were so taboo that no one was talking to each other. Leona and [Gerri’s friend] Joyce knew Gerri was in trouble but they didn’t talk to each other about it. Abortion was illegal, husbands were not challenged about the treatment of their wives, Leona and Joyce were afraid to talk about it.

I think every woman I interviewed for the film had an abortion, at least one. I have film of all of them telling their abortion story. I always leave time at the end of each interview and ask if there is something I left out or something they want to add. Judy [Gerri’s daughter] wanted to talk about her abortion. I decided I would include her story, and I didn’t include anybody else’s. She had more complicated feelings than the others, she was cautious with her words, and she felt she was going to be judged as a Christian. Some people who saw the film were turned off that I allowed that and I didn’t include the other stories. But to her there were spiritual consequences she felt she was facing, and that was a way to bring this side of the argument into the film.

Some of the most influential films I saw as a younger person were essay films, or films that have an essayist overlay created by the filmmaker that comments on what you are witnessing. I’ve never tried making an essay film. I’ve also never used a narrator. I don’t think I would be very good at it because someone has to write the narration, and I’ve never felt that I’m the authority on the subjects of any of my films. Not that I don’t do a massive amount of research. And as a filmmaker, I am selecting and editing the material that reveals a thesis. I do have opinions about the stories I tell. I suppose I prefer to present them through sound and image association rather than an outside voice.

How did you come across the suitcase of audio tapes that became the subject of Suitcase of Love and Shame? [The tapes had been exchanged by two people who were having a love affair in the 1960s.]

I told a friend of mine, Albert Steig, that I was looking for personal collections that had been abandoned that I could investigate for film. He regularly searched eBay and came across the listing for the suitcase. He called me and asked, is this something you’d be interested in? Of course I was, and he offered to bid for it through his eBay account. I love working with audio, so when I had the opportunity to work with the love and shame tapes, it was like going back to my roots working with projected slides and audio.

Before I watched it, I wondered how Suitcase of Love and Shame would work as a film since it is based on audio tapes. But the images are hypnotic, and keep you pulled into the recorded voices.

I’m glad you’re describing it that way, it was very intentional. At first, I was just going to do a sound piece without any images. You would listen to the narrative unfold in an audience with other people seated around you. But when I was looking for funding, I received support to make it into a visual work. So I started doing that, a bit reluctantly. I cut the audio first. I was always clear the images needed to be restrained, it was primarily about the audio, audio forward. The images would give you something to grasp when staring at the screen, but maybe not quite paying attention to what you’re looking at. You might be watching a scene, and the only thing you see is a shadow move. It is what you are imagining you are seeing that is important.

We filmed an audience watching Suitcase of Love and Shame. The cameras were placed in front of the screen, so you can see the audience lulled in their chairs. They are responding to what they are listening to more than what they are looking at. You are watching an audience listening to the film while hearing what they’re hearing.

Why did you want to make a film of the audience?

I liked the concept and I was hoping to turn it into an installation. I never installed it in a gallery, but it was in a theater space at the Museum of the Moving Image. There were set show times for Audience of Love and Shame, and people sat in the same seats other people sat in to watch the original film. I was glad to do it because it got closer to the audio theatrical experience I wanted to make in the first place.

Are there artists you have worked with who also live in Somerville?

One was a producer, writer and editor of Where the Pavement Ends, Khary Saeed Jones, who is a Professor of the Practice in Drama and Film at Tufts University. Another was a producer of Today the Hawk Takes One Chick, Tracey Kaplan. She is also the longtime director of the well-regarded Summer Street Preschool. There is also a filmmaker, author and curator who did some film work on Where the Pavement Ends, Ilisa Barbash. And of course there is my husband, Ken Winokur. He is best known as director, composer, and musician with Alloy Orchestra, and is currently directing and performing with Psychedelic Cinema Orchestra.

I’ll end by asking, do you have some favorite places in Somerville?

My backyard is one of my very favorite places. It is a garden we built ourselves. When we bought the house, the side and back was all paved. We tore it up and planted five trees, a massive garden and some pathways. When people go back there, they can’t believe it was once paved. I am quite fond of the Somerville Theater. Like many people, I really appreciate the Community Path. And I really love the different character, the village-y feelings of the different squares, Union Square, Magoun Square, Davis Square and the rest. The farmers markets in the winter and the summer are regular places we go. And many of the events that happen at Warehouse XI and the Armory.