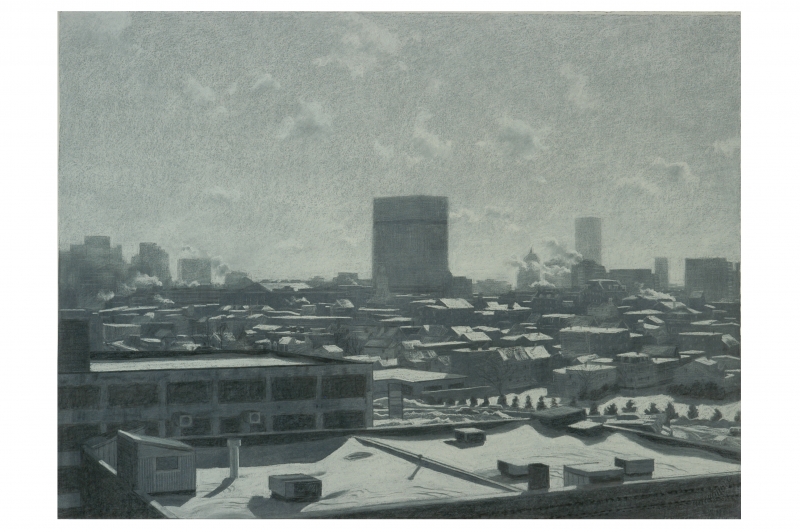

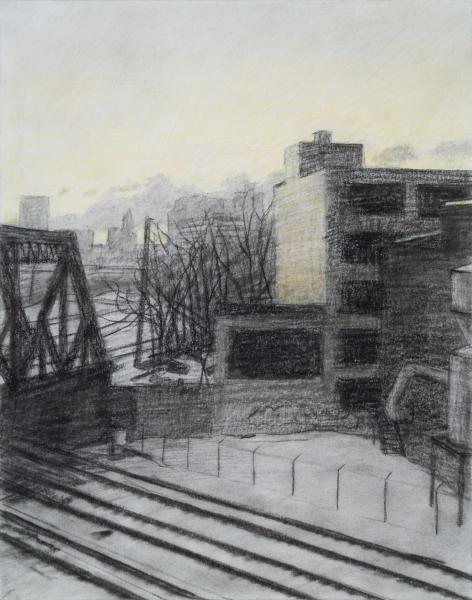

David Campbell is a realist painter based in Somerville’s Brickbottom Studios. His landscapes and cityscapes are held in many public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His work has been exhibited widely, including at Brandeis University’s Rose Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, Boston City Hall, the Boston Athenaeum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He taught adult education classes at the Maine College of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. David Campbell will have an exhibition at the Somerville Museum this fall.

David Campbell was interviewed by Charan Devereaux.

Do you remember when you knew you wanted to be an artist?

I was 21 years old; I had no thought of it before then. At the time, I was working on a surveying crew that traveled the country doing fieldwork for topographic maps. I don’t know where [the desire to be an artist] came from, it just arrived. I was in Arizona and quit the job and came back East.

Can you talk more about your work with the surveying crew?

I got the job right out of high school. All during my teenage years, I had terrific wanderlust, and this job filled the bill. So I joined the team and did it until I was 21. We traveled the country in pick-up trucks and trailers, constantly moving, living in hotels, eating in restaurants. I was working in a landscape everyday—desert, mountains, the Eastern forest—so becoming a landscape painter was a logical extension of loving the outdoors.

When I quit the surveying crew, I came home to Maryland, which is where I grew up, and I sent away for a catalog from the Art Students League in New York City. Its approach is modeled on the European tradition of choosing an artist to study under, which grew out of France and England in the 18th and 19th centuries.

I knew I wanted to be a realist, so I just picked one of the instructors. The catalog gave a brief account of each instructor and an image of their work. Back then [in 1957], it was so easy to do things. I found an apartment easily, on the Upper West Side, and enrolled with artist Robert Brackman. Five mornings a week I worked from live models in his studio, along with other students. Mr. Brackman came once a week to give critiques and that was really it. You learn what you can. You take instruction and follow the advice. I didn’t have to work—I had saved enough money on the surveying job. So I spent the afternoons drawing along the Hudson or in Central Park. On Saturdays, I took an anatomy class with a very good instructor, learning more about the figure. I came back home to Rockville for the summer, and got a job with a surveyor. Then I returned to the Art Students League for the next year.

In the middle of that year, I was drafted into the Army. I was not pursuing a degree, there was no program as such, so I had to be a soldier for the next two years. At the time, students seeking a college degree could defer military service. One of those years was in Korea, where I was in the infantry. It was the end of shooting in Korea and before the beginning of shooting in Vietnam. So it was the right year to be in Korea, if you were going to be there at all.

How did that time affect you?

It affected me as a person. In Korea, I had the chance to see another culture, what I could see of it being in the infantry, and having to be combat-ready, without much chance for liberty. I did get to know a Korean man who served the meals in our chow hall. I got friendly with him, and whenever I could, I went to the city of Seoul where he lived, and he showed me around. He took me to a Buddhist temple, to meet a master Korean calligrapher and to visit a working class family—a postal worker who lived with his wife and children. He also helped me meet a few art students. The Army allowed for R&R, rest and recuperation, in Japan. When I met these art students, they were famished for books on European art, and asked if I could get some books for them—sculptor Henry Moore was one of them. So I was very pleased to be able to do that when I visited Tokyo.

It affected me as a person. In Korea, I had the chance to see another culture, what I could see of it being in the infantry, and having to be combat-ready, without much chance for liberty. I did get to know a Korean man who served the meals in our chow hall. I got friendly with him, and whenever I could, I went to the city of Seoul where he lived, and he showed me around. He took me to a Buddhist temple, to meet a master Korean calligrapher and to visit a working class family—a postal worker who lived with his wife and children. He also helped me meet a few art students. The Army allowed for R&R, rest and recuperation, in Japan. When I met these art students, they were famished for books on European art, and asked if I could get some books for them—sculptor Henry Moore was one of them. So I was very pleased to be able to do that when I visited Tokyo.

I saw how the Army soldiers treated the Korean civilians as undeveloped people. But in my experience of Korea, I was seeing that in their great modesty, there was deep culture going back much farther than American culture, and how the U.S. soldiers in a large sense were culturally undeveloped.

When I returned from Korea, I had two weeks of leave before I went to a base in Georgia. My mother was very ill and I had those two weeks to spend with her. She had cancer, and she died while I was there.

In the meantime, my oldest friend from Rockville, who also went to the Art Students League, was exempted from the draft because he had diabetes. He had become pretty annoyed at the U.S., with all of its “isms”—racism, jingoism, philistinism. So he went to Italy, to Florence. We wrote letters, and he encouraged me to come there when I got out of the Army, which I did. At the time, a soldier was required to do six years—two years of active duty, two years of active reserve, and two years of inactive reserve. But I could leave the country, and I still had money from my surveying work, and the Army pay, which wasn’t much. This was during the time of the Berlin Crisis [1961] and the Cuban Missile Crisis [1962].

How long were you in Italy?

How long were you in Italy?

Seven years. I had no idea how long it would be. That was where I really started outdoor painting, landscape painting, on my own and all the time.

After seven years in Italy, I had become an all-out landscape painter, but the landscape of Tuscany was not mine. The cypress trees, the hills, the yellow adobe buildings with their red tile roofs, were not mine. I needed to be in my own landscape. This was during the late 1960s, with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy and the riot at the [1968] Democratic National Convention in Chicago. I was having feelings for my country, politically and topographically. It was my native landscape and that was where I should be.

At the same time, I learned my father was quite ill. We had always written letters while I was in Italy, but he never revealed he was sick. When I learned of his condition from my sister, I made arrangements to come back. He died the night I arrived at the airport in New York. I made my way to Rockville by train and by bus. The neighbors across the street had befriended him, and they told me he had died the night before. He lived all alone. The rest was the funeral and other relatives arriving. He had a rented house, so I disposed of that and sold the furniture.

I did not want to be in Rockville anymore, so I went back to New York City. I lived there on the Lower East Side and began to paint what was around me. I joined the Bowery Co-op Gallery in SoHo, which was just beginning to develop as a gallery neighborhood. I showed there the whole time I was in New York.

How did you make your way to Somerville?

How did you make your way to Somerville?

I met some people who lived in Gloucester [Massachusetts], they really talked it up as a good place. So one summer, I went there, and it was a really good experience. I was working as a freelance carpenter, house painter—an odd jobs man. Because of the fishing industry, Gloucester has a coherent architecture, which New York doesn’t have. It really appealed to me. It was the first American town I lived in after leaving my own town of Rockville at the age of 18. (Back then, Rockville was a very small town—now it is engulfed by the Washington suburbs.) So Gloucester was good, and I started painting the city and the ocean for two summers. Then I finally moved up there. I had gotten married, and I found an apartment with my wife Juliet and our daughter.

After some time, [Juliet and I] split up, and I looked for a new place to live. I answered ads in the paper seeking housemates to share apartments, and the one I got was in Somerville. I found a studio at the Rogers Foam Factory building, now known as Vernon Street Studios. I worked away at cityscapes. I’ve always drawn from what is right around me, within walking distance. So Somerville became my subject.

It appealed to me, the physical look of the city, the different neighborhoods. I just picked up the subject matter I had been pursuing in Gloucester, another New England town with its New England look. And I’m still pursuing that theme.

I remarried, and my wife Patsea Cobb, is also an artist. We were both among the original owners at Brickbottom Studios which was originally A&P’s New England cannery and bakery. At the time we bought [the building], it was a long term storage warehouse.

Eventually, we had two daughters, and we decided to leave the city and move to a small town, so we moved to Maine. We lived in Cape Elizabeth very near the ocean, where we had the advantages of the natural environment; nature preserves, forests. I started painting that, as well as the city of Portland [Maine]. We did not sell our studio at Brickbottom, we knew eventually we’d be back. We rented it out all those years. And when we found ourselves starting to get old and not wanting to maintain a house, we decided to come back to Somerville in 2014.

Brickbottom is a great arts community. We never really found a good arts community in Maine, but here we have it. Patsea is a figurative artist, so having figure drawing sessions is heaven for her. We are glad we came back. Our daughters were grown, so they didn’t live with us when we returned.

Brickbottom is a great arts community. We never really found a good arts community in Maine, but here we have it. Patsea is a figurative artist, so having figure drawing sessions is heaven for her. We are glad we came back. Our daughters were grown, so they didn’t live with us when we returned.

Quite a few of the original artists are still here. It has been really good to get to know them in our later years and see how they’ve developed and what’s happened in their lives. It is a very friendly community, a coherent community. The building has this wonderful, lush courtyard that over all these many years has become like a tropical garden. So in the summers, a lot of us meet out there and talk about things, talk about art. It is a great pleasure for both of us.

How has this recent time affected your work?

For me, my work is continuing to paint the city. Now, I often work from our windows. We are on the fourth floor with a huge panoramic view that goes from Harvard Square out to the new casino building, toward the ocean. Since I look out so often, I see it in all seasons. So I’ve done a series of paintings where the scene itself is the same, the same size painting, during each of the four seasons. The winter with its heavy snow, the autumn with autumn leaves. The one in spring is at dawn, with light just breaking across the city.

At my age [84], I don’t feel like going out too often and finding new sites. Though today, I’m going to do just that. Panoramas of Boston have always been of interest to me. I painted one from the Middlesex Fells and I recently found a place in Arlington, overlooking the city. I will start a painting there today.

David Campbell and Deb Olin’s exhibition “The Art of Observation” will open at the Somerville Museum in October 2020.